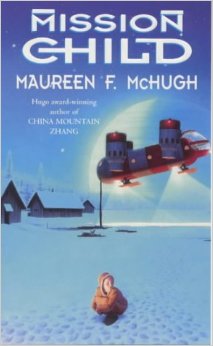

I want to begin the discussion of texts with a recommendation. At several conventions last year, I pointed to Mission Child by Maureen F. McHugh (Avon, 1998; Orbit, 1999) as the only good science fiction book about non-binary gender I had found. It remains my favourite.

The narrative focus of Mission Child is one person’s life: a very real life, one of reaction to major events and trying to find a path to survival and satisfaction. Janna lives on a world long ago settled and then forgotten by Earth, until recently. The return of people from Earth causes problems for the various inhabitants of the world. For Janna’s people, reindeer herders in the planet’s arctic region, it causes an influx of weapons that leads to violence, war and displacement. The hardships Janna faces—while surrounded by conflict, while fleeing it across a brutal winter landscape, while living in a refugee camp, while living as an immigrant in a city—are told very matter-of-factly, which gives the book a very personal intensity. The narrative is of a person experiencing events, without the grand over-arching direction of fiction.

This means that, true to many people’s lives, Janna does not arrive at a realisation about gender in a single moment.

At first, not being a woman is accidental: starved and wearing men’s clothes, Janna is identified by other people as a young man: “My mind was empty. I realized now while she was talking that she had meant me when she said ‘he’ to her husband, but now I didn’t know if I should correct her or not.” (pp96-97) On arrival at the refugee camp, Janna then gives the name Jan—a male name—and hides the signs that would reveal what is referred to as “my disguise” (p99). This is partly for survival as person without kin and partly to set Janna’s traumatic experiences in the past and partly because the identity comes to sit more comfortably on Jan than being a woman: “I felt strange to be talking about being a woman. I realized that I didn’t feel very much like a woman. I didn’t think it would be very smart to say that to him.” (p130)

Jan continues to prefer passing as a man when moving to a city to find work, until a medical examination, at which Jan fears being fired for lying—but finds a far more open attitude to gender. A doctor kindly and patiently presents the very confused Jan with the three choices of remaining as-is, taking hormones via an implant, or having surgery. Although the doctor speaks in terms of only male or female gender identities, he accepts without any fuss Jan’s disagreement with his suggested interpretation of Jan’s identity. He gives Jan space to explore and understand individual gender—a casual acceptance that is immensely refreshing.

This leads, years later, to Jan’s dissatisfaction with both gender identities: “Why were there only two choices, man and woman? ‘I am not man or woman,’ I said, ‘just Jan.’” (p356)

What I most like about Mission Child is that its intensely personal focus means that it doesn’t feel like a grand statement about non-binary gender. Jan’s gender is personal, a developing experience throughout the book, amid many other experiences. Jan’s whole life feels very real.

The book has weaknesses. It’s notable that Jan seems to be the only non-binary person in Mission Child, whose ambiguously-perceived gender is often met with questions and confusion (although this leads to acceptance, not violence). Given how many places and cultures Jan’s life leads to, this is a little strange. There’s also a surprising amount of sexism, specifically around gender roles and sex, which feels out of place for how far in the future this must be. These issues suggest a book a little too rooted in its author’s contemporary reality.

But, for me, its strengths make it stand out.

What Mission Child says about individual experience and the problems of inhabiting new planets is missing from a lot of science fiction works. What it says about one person’s experience of gender is quietly powerful and vital. It is just one point in the large constellation of gender experiences: a perfect place for a book to be.

It saddens me immensely that Mission Child has fallen out of print. I hope to see it in print again one day, but in the meantime it’s available from various second-hand sellers and I heartily recommend finding a copy.

Alex Dally MacFarlane is a writer, editor and historian living along the Thames estuary. Her science fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, The Other Half of the Sky and Stone Telling. She is the editor of Aliens: Recent Encounters (2013) and The Mammoth Book of SF Stories by Women (forthcoming in late 2014).

I have nothing to add to this beyond saying that I’ll look into tracking down a copy of ‘Mission Child’.

I’m just hoping to make sure that the first comment is something supportive of this series rather than the inevitable swarms of angry trolls that follow around anyone with any inklings of progressiveness.

Love this.

Now everybody go find it on Amazon and click “I’d like to read this book on Kindle“. and if B&N has the same thing, go do it there, too.

“There’s also a surprising amount of sexism, specifically around gender roles and sex, which feels out of place for how far in the future this must be. These issues suggest a book a little too rooted in its author’s contemporary reality.”

The society described seems much like the modern world in most ways, so I would assume that it is intentional.

Possibly of interest is Jo Walton’s 2009 review of Mission Child, at ‹http://www.tor.com/blogs/2009/08/colony-planet-home-maureen-mchughs-mission-child›.

love this book for all the reasons the column discusses (and more, such as what is appropriate technology, what does one need to thrive, when is action in self-defense morally ok).

but i must disagree with this:

this rests on the rather huge assumption that in the future, there won’t be sexism as we now know it. i think that’s an unsupportable assumption–we could just as easily go “backward” from where we are now (see The Handmaid’s Tale, among others).

anyway, McHugh is way, way better than to let something that big pass under her own radar.

“There’s also a surprising amount of sexism, specifically around gender roles and sex, which feels out of place for how far in the future this must be.”

Doesn’t seem out of place to me. Jan’s world is a harsh one where survival takes a lot of work. Those conditions are fertile soil for sexed-based division of labor, which in turn is fertile soil for sexism. In light of how often the two go together in human history, it would surprise me if sexism were absent under those conditions. It’s prosperity and plenty that breed progressive attitudes, not simply the passage of time.

Now, exploration of a society that practiced both sexed-based division of labor and egalitarian gender relations — that would take some imagining. Especially if it was a human society.

I will definitely add my voice to those who endorse this novel, I really enjoyed it very much. In regard to Ryan’s comment, I agree that there’s no particular reason to expect that the future would be the result of a straight line trajectory of today’s progressive values. In fact if history is anything to go by, straight progressions seem fairly unlikely.

I’m away from my copy of the book right now but I swear I remember some dialogue early on in Jan’s home village with her teacher, talking about how the settler communities chose certain social patterns based on what they felt would work best with the physical environments they were working in. Some of them decided to sex segregate their labor more than others. Or something like that. If I could get to my copy I’d look it up.

@5:

Interesting thing: did you know that, in medieval times and before, there was no racism based on skin color? At least a couple of Knights of the Round Table were people of color (one blacker-than-black-skinned Moor, and one guy whose skin color was a bright green). (Not to say there wasn’t racism, of course; Jewish people came in for most of it, but their skin color was pretty much the same as everyone else’s.) This is also touched upon in David Drake and Eric Flint’s Belisarius books.

Racism based on skin color only came about in the last few hundred years, and it will probably be with us for quite some time to come. So there’s one area where we all backslid culturally. We could very well backslide in others, too.

From the post:

Why would this be strange? Even counting all transgender people as “non-binary-gender” (and I understand most are in fact “binary gender”, their gender is just the opposite of their born sex) and physically intersex people, their occurence is under 1% in human populations. So it’s quite possible for Jan not to have come across another person like her, and (unless this were the topic of conversation—and the other person opened up to her) she wouldn’t know it if she had.

Specifically, the sexism in Mission Child looked very like sexism in our contemporary world; if there’s sexism in the future, it’s going to look different.

I do find it amusing(? or mildly terrifying?) that the idea of a future without sexism is hard to imagine for some people.

@@@@@ jcsalomon – The thing is that a) Jan meets a lot of people, with so much travelling around, and b) Jan talks to multiple people about gender – and no one at all seems to be non-binary, or have heard of someone who is. Some people might never meet a non-binary person (or know they have), but Jan’s life makes that a lot less likely.

I don’t know where that 1% number comes from but I’d certainly take it with a large grain of salt given how strongly most of our current cultures enforce the binary. Who knows what the incidence would be in societies that had different norms? I think its more likely that Jan doesn’t mean any other non binary people because Jan is pretty isolated a lot of the time. Especially when zie is working in the city, which seems to be the least binary of the societies.

@10: The idea of a future without sexism isn’t at all hard to imagine (at least for me), but getting there is going to be difficult. Making that happen will require a lot of changes to the way we do things now, and the people who benefit from the status quo will resist that. I don’t see that being any less true in Jan’s world than it is in ours.

As for the sexism in Mission Child looking a lot like the sexism irl, that makes sense if it stems from similar causes. The opportunity for works like this is to explore (or at least expose) those causes.

“Specifically the sexism in Mission Child looked very like sexism in our contemporary world; if there’s sexism in the future its going to look different.”

Now that does make sense to me. Sexism specifically, and bias generally has taken all sorts of different forms in the past. Robotech Master pointed out one of the differences, there are many others. So yes, it would make sense that the future wouldn’t look quite so much like now.